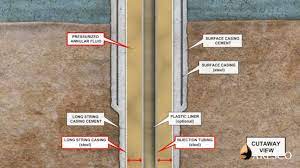

Carroll L. Lee, Peggy G. Lee, Lee Concho Valley Family L.P., Sandra Cagle, Jerry D. Lee, Larry G. Lee, and Matthew Lee v. Memorial Production Operating, LLC; Grandfield Consulting, Inc.; Boaz Energy, LLC; and Ivory Energy, LLC(No. 03-22-00063-CV; February 29, 2024) arose from the failure of a saltwater-disposal well on the Lees’ ranch in Coke County. They sued the owners and operators who operated under a lease first granted in teh 1940s. The well in question was drilled in 1957 for oil and gas production and became a saltwater-dosposal well in 2007. In 2014 the well failed, sending injected water spilling out onto the property. An investigation determined that the well tubing had deterioriated, that the mechanical packer intended to prevent backflow of injected water was less than the required 100 feet above the injection level, and that an additional packer installed 260 feet from the surface may have masked pressure anomalies indicating failure of the well (the additional packer was also “impermissibly within 150 feet of usable subsurface water).

Carroll L. Lee, Peggy G. Lee, Lee Concho Valley Family L.P., Sandra Cagle, Jerry D. Lee, Larry G. Lee, and Matthew Lee v. Memorial Production Operating, LLC; Grandfield Consulting, Inc.; Boaz Energy, LLC; and Ivory Energy, LLC(No. 03-22-00063-CV; February 29, 2024) arose from the failure of a saltwater-disposal well on the Lees’ ranch in Coke County. They sued the owners and operators who operated under a lease first granted in teh 1940s. The well in question was drilled in 1957 for oil and gas production and became a saltwater-dosposal well in 2007. In 2014 the well failed, sending injected water spilling out onto the property. An investigation determined that the well tubing had deterioriated, that the mechanical packer intended to prevent backflow of injected water was less than the required 100 feet above the injection level, and that an additional packer installed 260 feet from the surface may have masked pressure anomalies indicating failure of the well (the additional packer was also “impermissibly within 150 feet of usable subsurface water).

The Lees sued the owners/operators for damage to their cattle operation and their enjoyment of the land. After contested evidentiary rulings and dismissal of some of Plaintiffs’ claims, the trial court submitted several issues to the jury, which returned a no-liability verdict. The trial court entered judgment on the verdict. Plaintiffs appealed.

In an opinion by Chief Justice Byrne, the court affirmed. The court considered numerous issues, as follows:

- Did the trial court abuse its discretion by allowing two defendants to amend their pleadings to assert a “reasonably prudent operator” defense when that was not an issue in the case? The court answered no. The amendments were made before the close of discovery and more than 30 days before trial, and there was no indication that allowing defendants to argue the defense caused surprise or prejudice.

- Did the trial court err when it denied Plaintiffs’ summary judgment motion as to Ivory’s liability for negligence under § 85.321, Natural Resources Code? Again, the answer was no because the jury subsequently decided the same issue against Plaintiffs after trial.

- Did the trial court err when it granted summary judgments to Boaz II and Witt? No, because in their fourth amended petition, filed after the trial court granted those judgments, Plaintiffs dropped Boaz II and Witt from the case. This operated as a voluntary dismissal or nonsuit, and Boaz II and Witt were not properly parties to the appeal.

- Did the trial court abuse its discretion by granting summary judgment on the breach of contract claims to Grandfield and Ivory? No, because Plaintiffs produced evidence that they owned the surface but not that they were the successor owners of the mineral estate and, consequently, successor lessors of the mineral estate. Moreover, Grandfield conclusively established that he was not a party to the lease, having assigned all of his rights to subsequent operators well before the well failure.

- Did the trial court err by granting a directed verdict in favor of Memorial on Plaintiffs’ breach of contract claim? No, because one of the Plaintiffs, the Lees’ eldest son who operates the ranch, stated that the Lees did not own the mineral rights and that evidence was never rebutted. Since the Lees were not mineral-rights owners, they do “not have the right to lease the minerals and thus [were] not the successors to the original mineral lessors on the mineral lease.” Therefore, the alleged breach of the lease claim failed.

- Did the trial court commit reversible error in the jury charge? First, Plaintiffs argued that the trial court erred by submitting a charge on the “reaonably prudent operator” defense alluded to above. Unfortunately for Plaintiffs, although they periodically mentioned their objection to the defense, they did not object to the charge at the formal charge conference, thus failing to “make the trial court aware of their continued challenge to the inclusion of the defense in the jury charge.” They did not preserve the issue for appeal. The same went for Plaintiffs’ argument that the trial court improperly refused to charge on their intentional-nuisance claim and that it failed to include a Forest Oil instruction (i.e., that compliance with RRC remediation rules was not a defense to civil liability). Respecting the trial court’s refusal to submit a trespass charge, the court held that Plaintiffs offered no evidence of intent to operate a well with a shallow packer. Their case rested on negligence, not trespass, so it was not error for the trial court to exclude the charge. And even if it was error, the jury answered the negligence charge in the negative, rendering the error harmless.

- Did defendant Memorial’s attorney make an incurable jury argument? Memorial’s attorney pointed out to the jury that Plaintiffs sought a total of $170 million in damages to a $3.5 million ranch—and, “Oh, by the way, they get to keep the ranch. So they still have the ranch.” Plaintiffs argued that this argument prejudiced the jury by characterizing them as “rapacious, exploitative and immoral.” The court didn’t buy this argument, either, observing that the amounts of damages were in evidence and in Plaintiffs’ own argument. It also noted that Plaintiffs continued to live at the ranch during trial and intended to keep it, despite alleging more than $121 million for repairs, $1 million for dimunition in value, and $45 million for “annoyance and discomfort.” The court thus concluded that “a reasonable juror would not have understood the argument to be the moral indictment [Plaintiffs] argue it was and that the argument was not so extreme that an instruction or retraction could not remove any such effect.”

- Was the jury’s no-negligence finding supported by factually and legally sufficient evidence? Plaintiffs argued that the record established that Defendants were guilty of negligence pro se because they violated RRC regulations. But even so, the court pointed out, Plaintiffs must still prove proximate cause and that “the causation evidence [showed] that the injury would not have occurred if the negligence had not occurred.” This Plaintiffs failed to do because they presented no evidence that the RRC violations actually caused the failure or that any of the defendants knew about the illegal packer. Additionally, in response to Plaintiffs’ evidence that they overpumped saltwater into the well on several days prior to the accident, Defendants presented evidence of compliance with both monthly pumping limits and well-testing regulations that occurred before the failure, and that the well failure was due to the condition of the wellbore itself, which developed “over a longer term than the 17-day period during which [Defendants] overpumped saltwater.” The court thus concluded that more than a scintilla of evidence supported the jury’s no-negligence finding.

While this case doesn’t break any new ground, we think it merits notice for the meticulous manner in which the court breaks down the evidentiary and jury charge issues to affirm a defense verdict and judgment. Even though Plaintiffs presented evidence of various regulatory violations, which on its face might appear determinative on their negligence theory, they did not establish a causation chain from the violations to the well failure. The jury saw this, as did the court of appeals. But it also appears to us that the disproportionate amount of damages Plaintiffs sought in the case worked to their disadvantage, especially in view of the remediation conducted by Defendants in accordance with RRC regulations. When the operator cleans up the spill and still gets sued for $170 million in damages on a $3.5 million ranch, as Defendants pointed out, something is obviously out of whack.