Earlier this week we reported on House passage of HB 5214, which expands Texas antitrust law by rejecting the so-called “Illinois Brick Doctrine,” which provides that federal antitrust law does not permit indirect purchasers to assert antitrust claims and recover damages. Ill. Brick Co. v. Ill., 431 U.S. 720 (U.S. 1977). In that decision, however, the Court held that state antitrust laws could do so without running afoul of federal pre-emption. HB 5214 authorizes the attorney general to sue for damages to an individual or governmental entity’s business or property directly or indirectly caused by an antitrust violation. It also bill instructs the court “to take all steps necessary to avoid duplicative recovery from” a defendant against whom both direct and indirect purchasers assert claims.

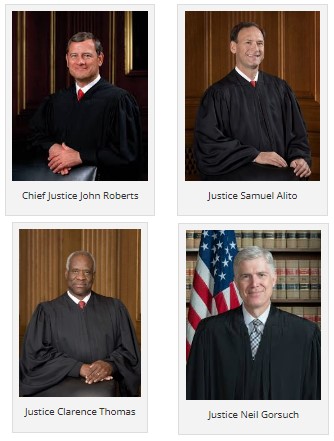

There are very strong policy reasons for maintaining Texas law as it has existed since 1983, when the Legislature enacted the Texas Free Enterprise and Antitrust Act. These reasons are rooted firmly in conservative legal principles. You don’t have to take our word for it—we’ll let U.S. Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch, joined by Chief Justice Roberts and Justices Thomas and Alito, conservative jurists if there ever were any, explain.

Justice Gorsuch’s dissent in Apple Inc. v. Pepper, 139 S.Ct. 1514 (2019) clearly sets out the rationale for the Illinois Brick Doctrine, which the Court affirmed in Pepper. The basis of HB 5214 is to allow the attorney general to step into the shoes of indirect purchasers of goods and services to recover costs that were allegedly “passed on” to the end consumer by the direct purchaser, the party directly harmed by the defendant’s anticompetitive behavior. As Justice Gorsuch pointed out, SCOTUS rejected this “passing-on” defense in a case called Hanover Shoe, Inc. v. United Shoe Machinery Corp.., 392 U.S. 481 (1968). He goes on to state the following:

While §4 of the Clayton Act allows private suits for those injured by antitrust violations, we have long interpreted this language against the backdrop of the common law. See, e.g., Associated General Contractors of Cal., Inc. v. Carpenters, 459 U.S. 519, 529-531 (1983). And under ancient rules of proximate causation, the “general tendency of the law, in regard to damages at least, is not to go beyond the first step. Hanover Shoe, 392 U.S., at 490, n. 8 (quoting Southern Pacific Co. v. Darnell-Taenzer Lumber Co., 245 U.S. 531, 533 (1918)). In Hanover Shoe, the first step was United’s overcharging of Hanover. To proceed beyond that and inquire whether Hanover had passed on the overcharge to its customers, the Court held, would risk the sort of problems traditional principles of proximate cause were designed to avoid. “[N]early insuperable” questions would follow about whether Hanover had the capacity and incentive to pass on to its customers in the shoe-making market United’s alleged monopoly rent from the separate shoe-making machinery market. 392 U.S., at 493. Resolving those questions, in turn, necessitate a trial within a trial about Hanover’s power and conduct in its own market with the attendant risk that proceedings would become “long and complicated” and would “involve[e] massive evidence and complicated theories.” Ibid.

We have taken the undoubtedly tedious liberty to quote Justice Gorsuch at length, citations and all. The point is, there can be no question that HB 5214 upends “ancient rules of proximate causation” in the precise way Justice Gorsuch warns against. Again, in Justice Gorsuch’s words, “there is nothing arbitrary or unprincipled about Illinois Brick’s rule or results. The notion that the causal chain must stop somewhere is an ancient and venerable one… If the proximate causation line is no longer to be drawn at the first injured party, how far down the causal chain can a plaintiff be and still recoup damages? Must all potential claimants to the single monopoly rent be gathered in a single lawsuit (and if not, why not)?” These are the questions we should be asking about HB 5214.

We do not here comment on HB 5214’s running partner, HB 5232. That bill raises the amount of civil fines in an antitrust enforcement action, which have remained the same since 1983. We can see the rationale for adjusting those amounts, but the way the bill accomplishes that seems arbitrary and unjust to us, particularly at the high end. The Notre Dame law professor who testified for the bills at both the House and Senate committee hearings cited the need to “deter” wrongdoers like Google and Apple. We have heard this deterrence argument for years in many contexts, but it simply perpetuates a false narrative that businesses are always looking for ways to wreck the competition and cheat their customers. Perhaps some do: that’s what the Clayton Act and state antitrust laws are for. But what they are not for is sacrificing “ancient and venerable” common law rules that protect defendants from the arbitrary exercise of state power. The Notre Dame professor also said something about “modernizing” the law. Well, we’ve seen enough proposals this session that dispense with basic procedural due process protections in the name of “modernization” to last us a lifetime.

The Texas Miracle happened in large part because we restored and adhered to the very “ancient and venerable” conservative tradition under attack in HB 5214. If Texas is going to start abandoning this tradition, we can expect rough waters ahead.