On June 9 Governor Abbott put his signature on HB 19, the hard-fought effort to establish a Texas business court along the lines of those in dozens of other states. The effort finally succeeded after not getting to the floor of the House in three consecutive sessions. We have reported on the contents of the bill for months, but now that HB 19 has gotten over the finish line, what can we expect in terms of implementation? When will a fully operational business court be up and running?

On June 9 Governor Abbott put his signature on HB 19, the hard-fought effort to establish a Texas business court along the lines of those in dozens of other states. The effort finally succeeded after not getting to the floor of the House in three consecutive sessions. We have reported on the contents of the bill for months, but now that HB 19 has gotten over the finish line, what can we expect in terms of implementation? When will a fully operational business court be up and running?

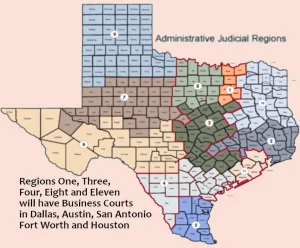

Let’s look at the details. First, the general effective date of HB 19 is September 1, 2024. “As soon as practicable” after that date, the Governor must appoint two judges in 5 of the bill’s 11 business court divisions. As reported elsewhere, these divisions cover primarily the major urban and suburban regions of the state, including the Dallas area (First Division), the greater Austin metro (Third Division), San Antonio and a good bit of the coastal plain (Fourth Division), Tarrant County and environs (Eighth Division), and, of course, the Harris-Fort Bend-Brazoria County conurbation (Eleventh Division). As you recall, HB 19 was amended on the floor to postpone the creation of a business court in the other six regions until 2026, contingent upon legislative reauthorization and funding in the 2025 session. Should the legislature do that, the Governor will appoint judges for the remaining divisions by September 1, 2026, but no earlier than July 1, 2025.

The initial appointees to the business court will thus undergo Senate confirmation during the 2025 regular session. The Texas Constitution (Art. 4, § 12) provides for confirmation by a two-thirds vote of members present (21 votes if all are present). In the event of recess appointments, which will be the case with business court judges, the Governor submits the nominees to the Senate during the first ten days of the following regular session. This section does not require the Senate to confirm a nominee, but if the Senate does not confirm, the Governor must resubmit the recess appointee or another nominee during the first ten days of each subsequent session until confirmation occurs. However, if the Senate in regular session doesn’t confirm or reject a previously unconfirmed recess appointee or another nominee, the appointee is deemed to be rejected at the end of the session.

Senate confirmation of appointees to the business court will be an interesting process. First, the two-thirds vote requirement means that at least two senators from the minority party have to go along with the governor’s appointment to get over the hump (if all 21 are present, that is). While that means that Democratic votes will be necessary in all five of the initial divisions, they become especially important given that four of the five divisions cover urban areas represented by one or more Democratic senators (it will be the same if the shoe was on the other foot, of course). On its face, consequently, it appears that potential appointees to the business court must be acceptable to senators from both parties in order to win confirmation. That is all to the good and should produce a very strong crop of initial appointees with a maximum level of education and experience and a minimum level of partisan political activity on one side or the other.

Put another way, if appointees are controversial for any reason, they are not likely to be confirmed. The confirmation process is supposed to work on a broad consensus basis, and HB 19 sets it up that way. For most potential appointees, then, the prospect of Senate confirmation should not deter them from seeking and accepting an appointment. One thing to think about, however, is that business court judges serve two-year terms, so if they are reappointed, they must go through the confirmation process each time they are reappointed. Again, this shouldn’t be a problem in most instances because subsequent confirmation will be based on the judge’s record on the business court bench, not just on his or her resumé. On the other hand, it is not inconceivable that political opposition to a business court judge might arise from the judge’s rulings, keeping in mind that 50% of the parties appearing in the court will lose. That is, of course, true in the elective system as well, but there is a very significant difference between getting re-elected by voters, the vast majority of whom don’t know who they’re voting for or against, or by a handful of senators who might be getting phone calls from unhappy and perhaps influential constituents. In any event, that’s something to watch out for as we go down the road.

But assuming everything goes as planned, we should have a functioning business court up and running in some parts of the state at the earliest by the end of next year. Things will be a bit unsettled as the appointees get organized and endure the confirmation process, but we presume that once the appointees are in place, there will be an interval in which, as required by HB 19, they will: (1) appoint the necessary personnel to operate the court, including court clerks, administrative staff, and attorneys (who are employees of the Office of Court Administration, not the business court itself); and (2) adopt rules of practice and procedure. At the same time (if not sooner), HB 19 directs the Texas Supreme Court to adopt rules of civil procedure, including rules governing “the timely and efficient removal and remand of cases to and from the business court; and (2) the assignment of cases to judges of the business court.”

Since the initial courts are created as of September 1, 2024, and apply to civil actions commenced on or after that date, the apparatus for accepting filings must be in place on that date. That does not mean, of course, that the courts in each division will necessarily be quite ready to start hearing motions on that date, but it does mean that parties can start getting in line on that date. It will be interesting to see what kind of race to the courthouse occurs in the period leading up to the effective date. We have traditionally seen a spike in filings right before the effective date of other major statutory changes, so we should not expect anything different this time. But there could also be a countervailing effect in which a plaintiff wants to file a qualifying action in the business court and, depending on limitations, delays filing until September 1, 2024. In other words, the effective date of HB 19 could cut both ways.

Another issue to take note of is the very high likelihood that the constitutionality of HB 19 will be challenged. The bill gives the Texas Supreme Court exclusive and original jurisdiction over such a challenge, but even if the Court strikes down the appointment process, the court will go on with retired or former judges or justices as we do in other cases every day. Either way, Texas businesses, at least in those parts of the state where the court will operate, now have a court with a qualified judge who can hear and rule on their motions much more quickly and efficiently than is currently the case. Even those who argue in the abstract that “appointed judges” are somehow more beholden to the political process than elected judges are (we would vigorously contest that argument) have to admit that HB 19 assures a fair confirmation process that requires a significant degree of political consensus on the appointments, not just a partisan rubber stamp. That is real progress for the cause of improving the quality and stability of the judiciary in the long run.

Will there be bumps along the way? Of course. But if it works, as we think it will, HB 19 will go a long way toward establishing the legitimacy of judicial appointment as an alternative to the current system. As proponents of judicial selection reform for nearly 40 years, TCJL has always maintained that the voters get the final say on changing the system. If the political parties are so certain that voters don’t want to “give up their right to elect judges,” then they shouldn’t worry about giving the voters the opportunity to express themselves to that effect. What’s encouraging is that HB 19 passed with at least some level of bipartisan support in both houses. There may have been many variables in play that allowed that to happen, but it is undeniable that 90 members of the House and 24 members of the Senate think that appointed judges are acceptable for a substantial category of high-stakes litigation. That’s a victory in our book one way or the other.