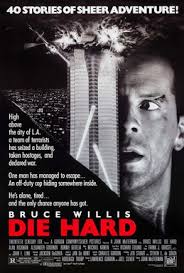

The San Antonio Court of Appeals has largely upheld a $1 million judgment in favor of the lessor of an upscale commercial aircraft in a contract dispute arising from an aircraft maintenance problem that delayed a flight chartered by Hollywood star Bruce Willis.

The San Antonio Court of Appeals has largely upheld a $1 million judgment in favor of the lessor of an upscale commercial aircraft in a contract dispute arising from an aircraft maintenance problem that delayed a flight chartered by Hollywood star Bruce Willis.

Saturn Aviation, LLC v. BMH Air,LLC (No. 04-23-00095-CV; July 2, 2025) arose from a contract dispute. In 2016, BMH Air and Maximum Flight Advantages (MFA) entered into a dry-lease (that is, an aircraft without a crew, maintenance, or insurance) agreement in which BMH transferred operational control over an Embraer EMB-135BJ aircraft to MFA. MFA then entered into a dry sublease agreement with Saturn obligating Saturn to provide necessary services to operate the plane as a charter. MFA agreed to reimburse Saturn for operating and other expenses. A few months later all three parties entered into a Subordination Agreement, backdated to 2016. BMH received priority interest in the aircraft over Saturn, and MFA agreed to BMH’s rights. In February 2017, in order to transfer its interests to a new entity, Evolution Jets, LLC, MFA and BMH executed an assignment of the Lease which assigned MFA’s rights, duties, and responsibilities to Evolution. MFA also assigned its rights and duties under the sublease to Evolution. If Evolution did not perform, however, MFA would remain responsible under the assignment of the original contract. Shortly thereafter, Evolution and Saturn executed an Amended Sublease in which Saturn promised to continue providing operational services, as well as new compensation terms. This agreement, too, was backdated to 2016.

At this point, things got interesting. Actor Bruce Willis chartered the Embraer to fly him from Ohio to New York. Before takeoff, the plane’s auxiliary power unit (APU) failed, though swift repairs allowed the plane to complete the flight. But BMH, MFA, and Evolution disputed Saturn’s maintenance of the plane, culminating in Evolution sending Saturn a notice of termination that grounded the aircraft. BMH and Evolution asserted breach of contract and tort claims against Saturn, seeking declaratory relief, damages, and attorney’s fees. BMH applied for a writ of sequestration to reclaim the aircraft. Saturn filed counterclaims for breach of contract, quantum meruit, unjust enrichment, and other affirmative defenses. The trial court granted BMH’s writ of sequestration and ordered BMH to place $375,000 into the registry of the court as a sequestration bond. After a prolonged bench trial, the trial court ruled for BMH and Evolution on their breach of contract claim. The court awarded BMH $498,109.28 in damages and an additional $78,596.66 to Evolution. It further awarded BMH attorney’s fees and expenses of $456,863.83 and allowed BMH to withdraw its sequestration bond. Saturn appealed.

In an opinion by Justice Brissette, the court of appeals affirmed in part and reversed in part. Saturn challenged the attorney’s fee award, the trial court’s breach of contract ruling, and BMH’s recovery of the cost of a replacement aircraft. Saturn further contended that that the Subordination Agreement failed for lack of consideration, was terminated by its own terms, and was not binding. Even if the agreement was effective, Saturn argued, it would be an insufficient basis for the damages awarded to BMH.

The court commenced with an analysis of whether the Subordination Agreement was supported by sufficient consideration. Reading the Subordination Agreement, it noted that the agreement provided a presumption of consideration. Saturn, unfortunately as it turned out, adduced the testimony of one of BMH’s owners, who averred that had Saturn not executed the agreement, BMH would have taken the aircraft back. Saturn didn’t offer any testimony to rebut this statement, so the court of appeals concluded that some evidence supported the trial court’s ruling that Saturn received consideration in the form of “clarity” of the contractual relationships and BMH’s “forbearance in not forcing MFA to terminate the Sublease with Saturn.” Because Saturn failed to overcome the presumption of consideration, the court overruled Saturn’s point of error.

Turning to Saturn’s contention that the Subordination Agreement automatically terminated when the parties assigned the lease, the court concluded that the purpose of the Agreement continued as long as Saturn retained exclusive rights to the operational control of the aircraft and MFA and Evolution retained the right to sublease the aircraft. Only if Saturn had somehow lost the right to operationally control the aircraft would the Agreement terminate by its own terms. Moreover, the Agreement expressly permitted MFA to assign its rights under the sublease, so doing so could not terminate the contract.

As for BMH’s recovery under the Sublease, Saturn asserted that BMH’s right of recourse against Saturn were limited by the Amended Sublease. The trial court’s found that BMH had the right to assert “any contractual remedies” for Saturn’s breaches, with BMH retaining all of the rights but none of the obligations of Evolution, and that Saturn was liable for all costs incurred by BMH relating to Saturn’s default. The court of appeals determined that BMH’s rights were not barred by the Amended Sublease. It didn’t matter that the trial court’s findings included only an impliedfinding that the Amended Sublease did not eliminate the Sublease and that the provisions in the Subordination Agreement therefore still controlled the relationship. The court of appeals accepted the implied finding by virtue of its authority to “imply all relevant facts necessary to support the judgment that are supported by the evidence” (citations omitted). But, at the same time, the trial court’s findings, which stated that the Sublease, not the Amended Sublease, was the source of Saturn’s liability was erroneous. The error, nevertheless, did not probably cause the rendition of an improper judgment because the provisions in the Sublease cited by the trial court in support of its finding of Saturn’s liability were virtually identical to the parallel provisions in the Amended Subliease. Consequently, the court of appeals couldn’t conclude that “the references to the Sublease instead of the Amended Sublease in the trial court’s findings probably caused the rendition of an improper judgment.” As for Saturn’s assertion that BMH had no rights in the amended Sublease, the court pointed to a subsection of the Subordination Agreement providing that BMH may assert the lessor’s rights under the under the Sublease, and MFA’s rights remained consistent even after the amendment of the Sublease.

The court also found that Saturn could be held liable for BMH’s damages under the Subordination Agreement. This finding was consistent with the language in the Subordination Agreement reserving several rights over the aircraft and providimg that the lessor had “all the rights and none of the obligations.” That language allowed BMH to pursue any remedy available to it under the applicable law under both agreements. The court further held that Saturn was not entitled to damages from Evolution or BMH, nor was it entitled to relief on its counterclaims. Additionally, Saturn’s point of error regarding Evolution’s entitlement to breach of contract damages was overruled because Evolution successfully bore the burden of showing that there was a deposit for services, the agreement had been terminated, and Saturn did not return the deposit after termination. Finally, the court upheld the trial court’s award of BMH’s attorney’s fees and costs.

The court of appeals handed Saturn a partial victory in concluding that Saturn could assert counterclaims against Evolution, although the agreements barred such claims against BMH. Even so, the court concluded that the evidence supported the trial court’s finding that Saturn failed to prove those claims. But, the court found that the agreements barred any damages for costs associated with substitution of replacement aircraft. Consequently, the trial court erred by awarded BMH replacement aircraft damages. Finally, the court overruled BMH and Evolution’s plea for lost profit damages on the basis of the plain text of the agreements.

All in all, the court of appeals upheld BMH’s damages award of nearly $500,000 for the necessary costs to inspect and repair the aircraft and to return it to an airworthy condition, nearly $40,000 for the costs of retaking possession of the aircraft and getting it into shape to return to service, and pre- and post-judgment interest. It reversed the nearly $200,000 award to BMH for reasonable and necessary costs of replacement aircraft, but upheld the $456,863.83 award of BMH’s attorney’s fees and costs. Evolution got its $60,000 deposit back from Saturn but didn’t get damages for reasonable and necessary incidental and consequential costs to assist BMH in retaking possession of the aircraft.

The moral of this story is to make sure your airplane is working before chartering it to a megamovie star. One wonders whether the dispute would have blown up this way if the passenger had been a mere mortal.

TCJL Research Intern Satchel Williams researched and assisted in drafting this article.